ABOUT NKH

What is Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia (NKH)?

NKH is a rare disorder which affects the brain and central nervous system. Patients with NKH are not able to process glycine (an amino acid). This leads to a build up of glycine in the body.

You might hear the term ‘Glycine Cleavage System’ (GCS) mentioned by your doctors. This is because patients with NKH have a GCS that does not work properly. This stops them from being able to process glycine correctly.

Glycine is important for our bodies in several ways. It is a chemical messenger, which means that it carries messages between the nerve cells in the body and the brain. Chemical messengers help the regulation of bodily functions – including breathing, digestion and moving muscles – by creating or stopping an electric signal. Glycine also contributes to other molecules that are used in our metabolism.

Without a working Glycine Cleavage System (GCS) the supply of one carbon molecules is also interrupted. One carbon molecules are important for Folate one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) – a metabolic process where enzymes are converted into more complex compounds. One carbon molecules and the FOCM system affects embryo development, DNA methylation and processing other proteins and vitamins.

Although NKH is considered to be a disorder that mainly affects the brain and central nervous system, symptoms can have effects on the whole body.

What causes NKH?

NKH is caused by genetic mutations in one of two sets of genes. In the case of ‘classic NKH’ (the most common type), these are known as the GLDC or AMT genes, which are the genes that build the system for processing glycine.

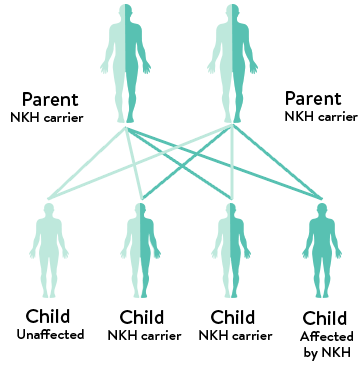

Most cells in your body carry two copies of each gene – usually one from each parent. To be affected by NKH, a child must have two mutations in the same gene. These two mutations might be the same or different. Mutated genes are genes that have permanently changed from their usual state. Typically, children inherit the mutation from their parents. This will generally mean that each parent is known as a ‘carrier’.

Carriers have only one mutation, and it is likely they won’t experience any symptoms of NKH. It’s also unlikely that they know they are carrying the gene mutation until they have a child with NKH. Very rarely, sometimes a mutation is spontaneous, which means it was not inherited from a parent and happened by chance.

How common is NKH?

It is hard to put an exact number on how many people are affected by NKH. This is mainly because NKH is rare, and records are not kept consistently. However, we are sharing some estimates that might be useful to give you some context.

Some studies suggest that 1 in 76,000 people worldwide are affected, while others report 1 in 60,000 in areas such as Canada. This number may increase to up to 1 in 12,000 in areas with smaller populations. In the UK, it’s estimated that there are between 50 – 100 people living with NKH.

Types of NKH

NKH can take several forms. We’ve listed these below, along with some of the differences between them, and what those differences might mean for you and your child.

Genetic variations: Classic NKH, Variant NKH + Transient NKH

Classic NKH

To be affected by NKH, a child must have two genetic mutations (usually one from each parent). When these mutations are found in a gene that is part of the Glycine Cleavage System (GCS), this is considered ‘Classic NKH’. In Classic NKH the mutations will be found in the GLDC, AMT and GCSH genes.

Variant NKH

This is when mutations are found outside the genes that support the Glycine Cleavage System (GCS). These mutations might be in genes that cause a mitochondria disorder, or a lack of lipoate or pyridoxal phosphate. These problems lead to damaged functionality within the GCS (though, this is an indirect effect on the GCS rather than a direct problem within a GCS gene). Both ‘classic’ and ‘variant’ types of NKH present with similar symptoms in patients.

Transient NKH

Transient NKH is where a child has the typical symptoms of NKH, but these resolve as they grow. This is a very rare type of NKH. A common cause is hypoxic-ischemic injury at birth which means that the brain doesn’t receive enough oxygen. Because transient NKH is not caused by altered genetics, symptoms can improve over time (and the levels of glycine are only temporarily higher than normal).

Onset: Newborn, Early and Late

Sometimes, the severity of NKH can be linked with the age at which NKH presents. Symptoms of NKH usually begin after birth, but can start later.

| Patients who present symptoms at age… | 0 to 2 weeks (‘neonatal’) | 2 weeks to 3 months | 3 months or later (‘late onset’) |

| Severe NKH | 85% of patients | 50% of patients | 0% of patients |

| Attenuated NKH | 15% of patients | 50% of patients | 100% of patients |

Severity: Severe NKH and Attenuated NKH

The way in which NKH presents can vary a lot between patient to patient. This depends on a number of factors, including the location of the mutation in the gene. Some children might be

able to process a small amount of glycine, or partly process glycine, while others can’t process glycine at all. This means that each patient with NKH is an individual and how they experience symptoms, medications and outcome is unique. Severity is a way of defining how NKH can present (the extent of the symptoms and their effects).

There are two broad categories in which NKH severity is defined:

– Severe NKH. Typically, patients with severe NKH are not able to process, or part process any amount of glycine.

– Attenuated NKH. Patients with attenuated NKH are able to partly process glycine, or process only a very small amount. Attenuated NKH is split into three sub-categories: attenuated poor, attenuated intermediate and attenuated mild/good.

Attenuated means that the effect (in this case, glycine toxicity) is reduced.

Both categories experience a wide range of symptoms that can be difficult to manage. It is important to note that Attenuated NKH (particularly attenuated poor, or attenuated intermediate) should not be considered ‘more mild’ than Severe NKH. While the symptoms are often different, attenuated symptoms are often difficult to manage and do not always have better outcomes than patients with severe symptoms.

Symptoms of NKH

Because each mutation is in a different part of the gene that affects NKH, each child with NKH is unique and symptoms can be very different for each patient. They also may appear at different

points in a child’s life, as their brain and body grow.

We know first hand how upsetting and distressing it can be watching your child suffer with any of these symptoms, especially when they are difficult to identify or hard to treat. We strongly recommend you find ways to support your mental health (such as therapy, or respite) to help you manage stressful times.

For each of the symptoms, we list medical terms that you might hear used, and offer an explanation of those terms in language that is easy to understand. This is so you can recognise things your doctor may say, while also having an idea of what your child is experiencing.

What are the most common symptoms?

There are many different symptoms of NKH and – because of unique mutation placement – not all patients experience them all. The most common symptoms of NKH are those which appear in more than 3 in 10 patients.

The four major groups of symptoms are:

- Cognitive (brain) disorders

These are symptoms related to the brain and covers a range of symptoms, such as delayed development, hyperactivity and aggressive behaviour, among others. - Seizures

Children (and adults) with NKH often experience multiple kinds of seizures. These seizures are often intractable, which means they don’t respond to medication. Many children with NKH live with daily seizures.

It might also include status epilepticus. This is a type of coma in which epileptic fits follow one another without recovery of consciousness between them. - Muscle and movement dysfunctions

Muscle and movement dysfunctions might include:- lethargy (a state of sleepiness or unresponsiveness and inactivity)

- spasticity (a medical term for progressive stiffness of muscles)

- dystonia (periods of abnormal muscle tone and posture)

- chorea (involuntary and unpredictable muscle movements)

- inability to sit, stand or walk without support

- hypotonia (having very low muscle tone, particularly in the torso)

- symptoms related to feeding, with a poor suck or failure to feed,

or eat orally.

- Brain malformations

This can mean things like a thinner Corpus Callosum (the part of the brain that connects the left side to the right side).

Symptoms by severity/onset

It’s important to remember that each child is unique, and is likely to present differently, particularly across severity and during in the neonatal period (in the first two weeks). We would recommend looking through the symptoms for the type of NKH diagnosis that you have, to give a more specific idea of what this might look like in your child.

Symptoms you may see during the newborn phase

Some children will present with NKH as a newborn, within the first few days of birth. If this is the case, you may see some of the following symptoms:

- Hyperglycinemia (high levels of glycine in the body).

- Respiratory distress. This is where the patient has difficulty breathing and may need support to breathe.

- Apnea (this means that the patient stops breathing for a short period of time).

- Progressive muscular hypotonia (a lack of muscle tone, which means that children may appear floppy when they are held).

- Myoclonic jerks (this is a sudden and involuntary jerking of muscles or a group of muscles).

- Brain malformations, which may include:

- Hydrocephalus (a condition which puts pressure on the brain tissues through fluid building up) and/or ventriculomegaly (areas of the brain become bigger than they should be, due to this fluid building up).

- Thin/agenesis (meaning that it has not developed as an embryo) of corpus callosum.

- Myelination pattern changes (this is an essential process for cells to develop and for motor functions like movement and processing sensory information).

- Coma. This means the patient is in a state of unconsciousness, where they are unresponsive and cannot be woken.

- Burst Suppression Pattern on an EEG (electroencephalogram). This is a type of brain function where there is lots of activity, then none at all. An EEG is a test used to measure this activity.

- A Burst Suppression Pattern is typically followed by Hypsarrhythmia (chaotic brain activity) or Infantile Spasms (a particular type of seizure that occurs in babies that last one to two seconds each).

- Poor suck/failure to feed.

- Low body temperature.

Symptoms of Severe NKH

Some children with severe NKH may never make developmental gains, and may have a Developmental Quotient (DQ) of less than 20 (this means that they may reach the developmental age equivalent to 6 weeks to 3 months).

Symptoms will also vary depending on how the patient responds to treatment. For those who do make developmental gains, they may gain the ability to smile and the ability to roll from back to side, or side to front.

From both clinical research and the knowledge of the NKH community, patients with severe NKH may show the following symptoms:

- Cortical blindness (this is a type of blindness that does not have a cause that relates to the eye) or other visual impairments. It’s also known as CVI, Cortical Vision Impairment.

- Scoliosis (which is a twisting or curving of the spine) and/or hip dislocation. You might hear this being referred to as either hip subluxation, (which means the hip bone is not fully inside the socket) or hip dysplasia (where the hip is dislocated).

- Profound mental retardation (severe learning disabilities) or cognitive impairment (trouble with everyday brain functions like remembering, concentrating, learning new things, or understanding the world around them).

- Seizures that become increasingly difficult to treat after the first year or seizures which are known as ‘intractable’ (this means seizures that do not resolve easily with medication). Examples of this may include myoclonic seizures (a seizure type that causes sharp and uncontrollable muscle movement), and multifocal clonus (this type of seizure involves jerking movements in one limb, which move to another).

- Global developmental delay (this is when a child takes longer to reach milestones in their development than others of the same age). This includes every aspect of their development: physical, social, emotional and intellectual.

- There are a range of muscle movement control disorders that the patient may experience. These might include:

- Spasticity (which is abnormal muscle tightness due to prolonged muscle contraction).

- Dystonia (a condition that causes muscles to contract involuntarily).

- Ataxia (a loss of muscle control in the arms and legs).

- Chorea (jerky movements which are sudden, unintended and uncontrolled in the arms, legs and facial muscles).

- Hypotonia (having very low muscle tone, particularly in the torso)

- Dysphagia (this is a medical term for difficulty swallowing, and is something that most patients with severe NKH will experience).

- Lethargy and prolonged periods of sleep, or the inability to relax and sleep.

- Repeated infections, which may include chest or urine infections, among others.

- Tube feeding, via nasal gastric (ng-tube – a tube inserted in the nose, but fed down to the stomach and held in place using tape on the face), gastrostomy (g-tube or button – a small medical device surgically inserted in the abdomen wall, directly connecting to the stomach) or jejunostomy (jeg tube – similar to a g-tube, feeding into the bowel, bypassing the stomach).

Symptoms of Attenuated NKH

Children with Attenuated NKH do make developmental progress, but the amount of progress varies across the different types of NKH. Developmentally, some of these children can learn to reach and grasp, use sign language and interact with carers.

Attenuated Poor NKH

This type of NKH sits between severe NKH and attenuated NKH. In terms of development, these patients will have a DQ of less than 20. They may learn to grasp objects, to sit with support, and can have limited interaction in some areas. They may learn to eat small amounts orally with support, and have a few signs/vocal cues to communicate.

As well as some symptoms from the severe NKH list, these patients with Attenuated Poor NKH might also experience:

- Spasticity, although at a lower level than severe NKH.

- Severe lethargy may be provoked by fever and/or infection.

- Seizures can occasionally (but not always) be controlled using medication. Abnormal brain activity (the cause of seizures) that is not able to be controlled with medication is often a sign of a poor overall outcome.

- Patients may also experience choreic movements (these are sudden, unintended, and uncontrollable jerky movements of the arms, legs, and facial muscles).

Attenuated Intermediate NKH

Patients in this group tend to have a DQ of 20-50. They can learn to walk and communicate (this can be verbal speech, but is more typically sign language). They can grasp items with purpose and eat orally on their own. Specific symptoms can include:

- Bursts of choreatic movements and hyperactivity.

- Where the patient does experience seizures, these can usually be well treated/controlled with medication.

- In the NKH community, it is common to hear of children with attenuated NKH experiencing gastric issues or severe stomach pain.

- Cognitive Disorders, which might appear as:

- ADHD (Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) people who have ADHD have symptoms of inattention. Inattention means keeping focused on things and staying organised. They also have symptoms of hyperactivity, and impulsivity (which means acting without thinking or self-control).

- Aggressive behaviour.

- Hyperactivity is common and harder to treat. This means that a patient has increased movement, acts impulsively, is able to pay attention for less time, and is distracted easily.

- Hypoactivity (slowed/decreased motor ability or other skills).

- Autism (this is a disorder that affects how people behave, communicate and learn and interaction with others).

- Sexual impulsivity.

- Stranger anxiety.

Attenuated Intermediate NKH

This group of patients usually have a DQ of over 50. They make substantial developmental progress and do not have epilepsy. They can sometimes attend mainstream school classes, get jobs, raise families and live independently. Specific symptoms for this type of NKH can include severe lethargy following infections or illness, and they may have ADHD.

NKH Prognosis

Prognosis means the likely course, or the expected outcome. There is no cure for NKH and current treatment is for symptom management only. The life expectancy of a child born with NKH can vary, depending on the form of NKH and the age of onset (when the symptoms first appear).

Research studies suggest around one in three children born with NKH will die before their first birthday. For those that survive their first year, the average age of death depends on the onset (either neonatal: in the first 28 days of life, or infantile: in the first 2 to 12 months) and severity.

It’s thought the median age of death for the severe neonatal onset form is around 4 years and around 8 years for the severe infantile form. Median means the ‘middle’ value (the value for which half of the observations are larger and half are smaller).

For those with attenuated NKH, the survival rate is thought to be much better, but there is little to no research on what that might look like. In the NKH community, it’s thought that one in ten

children with attenuated NKH are likely to die before their tenth birthday.

However as medical treatment advances, some patients with NKH live much longer. There are people living with severe NKH well into adulthood. The oldest person with severe NKH is in their 40s.

Most children diagnosed with NKH experience some form of disability, depending again, on the onset and severity. The more severe the NKH, the more profound the physical disability. With attenuated forms, there are often difficult behavioural disabilities.

There has been lots of funding raised by families and organisations to support research in NKH, especially in growing our understanding of NKH and how to treat it. These advances have

generally been in symptom management, such as reducing seizure frequency or treating infections, but also include medications that reduce glycine levels and exploring gene therapy treatment options.

Please know that while parenting a child with an NKH diagnosis can be hard, there is still lots of joy and love to be had too.

The information on this website is certified by the PIF TICK, which indicates health information you can trust. The independent trust mark lets you know information is evidence-based, up-to-date and easy to use and understand.